Billingsgate is the great fish-market, which is principally supplied by fishing-smacks and boats coming from sea up the river Thames, and partly by fresh fish brought by land carriage from all the southern and western parts of England; vast quantities of salmon also reach Billingsgate from Scotland by the steam packets, curiously packed in boxes of ice. The quan tity of fish consumed its the metropolis is on the increase, on account of the very moderate price which it now generally bears. There are, on an average, annually brought to Billingsgate market 2500 cargoes of fish, of 40 tons each, and about 20,000 tons by land carriage; in the whole 120,000 tons. The supply of poultry being inadequate to a general consumption, and the price consequently high, that article is mostly confined to the tables of the wealthy. Game is now publicly sold, and a considerable quantity, by presents, is consumed by the middling classes. Venison is sold, chiefly by pastry cooks, at a moderate rate; but the chief consumption, which is considerable, is amongst the gentry and proprietors of deer-parks. The annual consumption of wheat in London may be averaged at 900,000 quarters, each containing eight Winchester bushels; of porter and ale, 2,000,000 barrels, each containing thirty-six gallons; spirits and compounds, 11,000,000 gallons; wines, 65,000 pipes; butter, 21,000,000 lbs.; and cheese 26,000,000 lbs. The quantity of coals consumed is about 1,800,000 tons. About 9600 cows are kept in the vicinity of London for supplying the inhabitants with milk, and they are supposed to yield nearly 7,900,000 gallons every year: even this great quantity, however, is considerably increased by the dealers, who adulterate it by at least one fourth with water before they serve their customers.

Mogg's New Picture of London and Visitor's Guide to it Sights, 1844

BILINGSGATE. A gate, wharf and market a little below London

Bridge, appointed 1. Eliz. c.ii: "an open place for the landing and

bringing in of any fish, corn, salt stores, victuals and fruit (grocery wares

excepted), and to be a place of carrying forth of the same or the liek, and for

no other merchandise;" and made, pursuant to 10 & 11 William III, c.24,

on and after May 10th, 1699 "a free and open market for all sorts of

fish."

... The coarse language of the place has long been

famous:-

"There stript, fair Rhetoric languish'd on the ground;

His blunted arms by sophistry are borne,

And shameless Billingsgate her robes adorn."

Pope, The Dunciad, B. iv.

The market opens at 5 o'clock throughout the year. All fish are

sold by the tale except salmon, which is sold by weight, and oysters and

shell-fish, which are sold by measure.

... Here every day (at 1 and 4), at the "One Tun

Tavern" looking on the river, a capital dinner may be had for

eighteen-pence, including three kinds of fish, joints, steaks, and bread and

cheese.

Peter Cunningham, Hand-Book of London, 1850

see also David Bartlett in London by Day and Night - click here

Billingsgate Fish Market is in Lower Thames Street, adjoining the western

side of the Custom House; it has its own port for the landing and sale of all

kinds of fish on a most extensive scale. Fish from all parts of the coast and

from foreign ports are here sold. The lobster from Norway is a most valuable

article of import; a very large sum annually is remitted by the salesmen for

this fish alone. This market is under strict, yet judicious management by city

authority, and all tainted fish unfit for human food is destroyed, and the

vendor fined for his attempt at imposition. This market is an exception to the

foregoing remarks; it has lately been much improved by the city architect, Mr.

Bunning, who has attended strictly to its ventilation, drainage, and sanitary

regulation. This object is effected by mechanical means. Mr. Bessemer, the

engineer, has constructed a centrifugal machine for exhausting the air: it

consists of two discs of iron, each eight feet in diameter, and having a central

opening of half that size, and placed on a shaft, 2 ft. apart from each other,

and attached by eight radial partitions, forming a series of segmental chambers

around the axis; a communication is established between the central openings of

this disc and the place to be exhausted, by several underground channels

branching off to different points, where openings are formed for the inlet of

the air, while the external diameter of the discs communicate with an air shaft

leading upwards above the roof of the building, where the foul air is dispersed.

When a rapid rotary motion is communicated to the disc the air contained In its

segmental chambers immediately acquires centrifugal force, and escapes at the

outer edge of the disc, while new portions of air rush to the centre of it, from

all the numerous inlets before referred to, and thus fill up the vacuum formed

by the escape of it at the periphery ; so that a continuous and powerful action

is kept up, carrying out of the market at least 50,000 cubic feet of foul air

per minute, the space previously occupied by which is immediately reoccupied

with fresh air from the open front next the river.

Upon this same centrifugal principle Mr. Bessemer has recently patented a

pump of the most powerful description, for lifting and forcing water, which is

here applied for the supply of water for washing the market; and filtered water

for cleaning the fish, and the general use of the market people, is also

supplied by means of this small though powerful pumping machine. Two tons of

water per minute are lifted 35 ft. high from filters in the bed of the Thames,

and from thence delivered into a fountain In the upper market; 1¾

ton per minute of unfiltered water is lifted from the Thames, and passes in a

constantlv-flowing stream along a series of gutters formed at short Intervals

along the whole surface of the market, and covered over with gratings, so that

the drainage from the numerous fish-stalls, uniting with the water flowing in

these gutters, is immediately carried off, while 1 ton per minute of water is in

like manner distributed throughout the lower market, from which it is again

pumped out by the tame apparatus, and discharged into the Thames.

The quantity of water raised, it is said, by this small pump, is 77,000

imperial gallons per hour; and at the price charged by the water companies,

would exceed 4000l. per annum. Notwithstanding there are four different

elevations to which the water has to be raised in such vast quantities, and that

some part of it is filtered, some in the state of ordinary Thames water, and the

other part consisting of the foul drainage water from the lower market, one

apparatus deals with these different masses of water without any intermixture ;

and the entire apparatus consists only of one single revolving piece,

having no no rubbing surfaces, and fitting closely nowhere except

at its axis, and is contained in a cast-iron case, and without any

reciprocating parts whatever, not even the alternating motion of a valve ; nay

more, the same axis on which the centrifugal water discs are fixed, nerves also

for the axis of the large air disc used for ventilation; and thus by the simple

rotation of one revolving piece all the effects before referred to are produced,

motive power being applied from a very simply-constructed oscillating steam

engine of 16-horse power, the fly-wheel of which is made broad enough to carry a

gutta-percha strap, passing over a drum in the centrifugal pump shaft, and thus

communicating a sufficiently rapid motion.

London Exhibited in 1852, 1852

YESTERDAY morning we went to London Bridge and along Lower Thames Street, and quickly found ourselves in Billingsgate Market,—a dirty, evil-smelling, crowded precinct, thronged with people carrying fish on their heads, and lined with fish-shops and fish-stalls, and pervaded with a fishy odour. The footwalk was narrow,—as indeed was the whole street,—and filthy to travel upon; and we had to elbow our., way among rough men and slatternly women, and to guard our heads from the contact of fish-trays; very ugly, grimy, and misty, moreover, is Billingsgate Market, and though we heard none of the foul language of which it is supposed to be the fountain-head, yet it has its own peculiarities of behaviour. For instance, U. tells me that one man, staring at her and her governess as they passed, cried out, ‘What beauties !‘—another - looking under her veil, greeted her with ‘Good morning, my love!’ We were in advance, and heard nothing of these civilities.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, The English Note-Books. Nov. 15th 1857

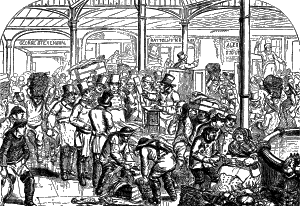

The busy scene within the market, between th

e hours of 5 and 7 in the morning, is one of the marvels of the metropolis. Billingsgate is the only wholesale fish-market in London, and it may therefore be imagined how great must be the business transacted within its walls. Of old nine- tenths of the supply came by way of the river. . now the railways are day by day supplanting smacks, and in many cases steamers.. . Nearly one-half in fact of the fish-supply of London is hurried in the dead of night across the length and breadth of the land to Billingsgate, and, before the large consumers in Tyburnia and Belgravia have left their beds, may be seen lying on the marble slabs of the fishmongers, or penetrating on the barrow of the costermonger into the dismal lanes and alleys inhabited by ‘London Labour and the London Poor’. Let the visitor beware how he enters the market in a good coat, for, as sure as he goes in in broad cloth, he will come out in scale armour. They are not polite at Billingsgate, as all the world knows, and ‘by your leave’ is only a preliminary to your hat being knocked off your head by a bushel of oysters or a basket of crabs...Dr Andrew Wynter, ‘The London Commissariat’, Quarterly Review, No. cxc, vol. xcv 1854

BILLINGSGATE

MARKET, the great fish depot of the Metropolis, is now held within the precincts

of a picturesque red-brick building, designed by Mr. Bunning, and erected in

1849-53. The name is probably derived from an old settlement of the Saxon Belingas,

who formerly possessed this "gate," or "opening," to the

River. From the earliest times a market has been held here, and the laws of

Athelstan record that at this place a toll was levied upon fishing-boats.

William III. made it "a free and open market for all sorts of fish,"

in 1699.

The scene presented here, at early morning, is full of life

and animation. Fishmongers from all parts of the Metropolis, and from many of

the principal inland towns, gather around the salesmen's stalls, which are

loaded with salmon from Ireland, Scotland, and Norway; or mackerel from the

"narrow seas;" or turbot from the English Channel; and sales are

effected, by Dutch auction, in a remarkably simple and expeditious manner.

Cruchley's London in 1865 : A Handbook for Strangers, 1865

see also James Greenwood in Low-Life Deeps - click here

The

Market, for many years, consisted of a collection of wooden pent-houses, rude

sheds, and benches it commenced at three o'clock A.M. in the summer and five in

the winter: in the latter season it was a strange scene, its large flaring

oil-lamps showing a crowd struggling amidst a Babel din of vulgar tongues, such

as rendered "Billingsgate" a byword for low abuse: "opprobrious,

foul-mouth language is called Billingsgate discourse." -(Martin's Dictionary,

1754, second edit.) In Bailey's Dictionary we have "a Billingsgate,

a scolding, impudent slut. Tom Brown gives a very coarse picture of her

character; and Addison refers to debates which frequently arise among the ladies

of the British fishery. She wore a strong stuff gown, tucked up, and showing a

large quilted petticoat; her hair, cap, and bonnet flattened into a mass by

carrying a basket upon her head; her coarse, cracked cry, and brawny limbs, and

red, bloated face, completing a portrait of the "fish-fag" of other

days.

Not only has the virago disappeared, but the market-place has

been rebuilt, and its business regulated by the City authorities, with especial

reference to the condition of the fish; and in 1849 was commenced the further

extension of the market. There is no crowding, elbowing, screaming, or fighting,

as heretofore; coffee has greatly superseded spirits; and a more orderly scene

of business can scarcely be imagined. The market is daily, except Sundays, at

five A.M., summer and winter, announced by ringing a bell, the only relic of the

olden rule. The fishing-vessels reach the quay during the night, and are moored

alongside a floating wharf, which rises and falls with the tide. The

oyster-boats are berthed by themselves, the name of the oyster cargo is painted

upon a board, where they arc measured out to purchasers. The other fish are

carried ashore in baskets, and there sold, by Dutch auction, to fishmongers,

whose carts are waiting in the adjoining streets. The wholesale market is now

over; the bummarees supply the costermongers, &c.

All fish is sold by tale, except oysters and shell-fish,

which are sold by measure, and salmon by weight. In February and March, about

thirty boxes of salmon, each one cwt., arrive at Billingsgate per day; the

quantity gradually increases, until it amounts in July and August, to 1000 boxes

(during one season it reached to 2500 tons)-the fish being finest when it is

lowest in price. Of lobsters, Mr. Yarrell states a twelvemonths' supply to be

1,904,000; of turbots, 87,958. The speculation in lobsters is very great: in

1816, one Billingsgate salesman is known to have lost 1200l. per week,

for six weeks, by lobsters! Periwinkles are shipped from Glasgow, fifty or sixty

tons at a time, to Liverpool, and sent thence by railway to London, where better

profits are obtained, even after paying so much sea and land carriage. Sometimes

there is a marvellous glut of fish: thus, in two days from 90 to 100 tons of

plaice, - soles, and sprats have been landed at Billingsgate, and sold at two

and three lbs. a penny; soles, 2d.; large plaice, ld. each.

A full season and scarce supply, however, occasionally raise

the price enormously; as in the case of four guineas being paid for a lobster

for sauce, which, being the only one in the market, was divided for two London

epicures! During very rough weather, scarcely an oyster can be procured in the

metropolis. In the Times, Nov. 9, 1859, we read: "In consequence of

the gales which have recently prevailed, the price of fish has risen so much,

that cod-fish fetched the enormous sum of- 1l. 15s., yesterday

morning in Billingsgate market."

Mackerel were, in 1698, first allowed to be cried through the

streets on a Sunday; but, by the 9 and 10 Victoria, passed August 8, 1846, the

sale of mackerel on a Sunday was declared illegal.

The wholesale fish-trade of Billingsgate having greatly

increased in 1854, Mr. Bunning, the City architect, completed a sub-market on

the site of Billingsgate Dock; the carriage of fish by railway to London having

greatly superseded the use of sailing vessels for that purpose. A new granite

wharf-wall extends the entire river frontage of the market; and the foundations

of the fish-market were constructed on the blue clay beneath the bed of the

river, without the aid of a coffer-dam.

Few persons are aware of the great consumption of fish in the

metropolis. In the Parliamentary Report on the Sea Fisheries, 1866, is a

calculation showing that nearly as much fish as beef is consumed in London.

About 90,000 tons of fish are brought yearly, of which some 80,000 tons are

large fish, the remainder being whiting and small fish.

John Timbs, Curiosities of London, 1867

Summer or winter, light or dark, rain or shine, it matters

not; as the clock strikes five, the bell rings and the market opens. The Clerk

of the Market, the representative of the Corporation, is there, to act the part

of major-domo; the vessels are there, hauled up in tiers in the river, laden

with their silvery cargoes; the porters are there, running to and fro between

the ships and the market; the railway vans and carts are there, with fish

brought from the several railway stations; the salesmen are there at their

stands or benches; and the buyers are there, ready to buy and pay. As yet all is

tolerably clean. There is, of course, that "fish-like smell" which

Trinculo speaks of; but Billingsgate dirt and Billingsgate vilification have not

yet commenced. The street dealers, the costermongers or "costers,"

have not yet made their appearance; they wait till their "betters,"

the regular fishmongers, have paid good prices for choice fish, and then they

rush in to purchase everything that is left. It is a wonderful scene, even at

this early hour. How Thames Street can contain all the railway vans that throng

it is a marvel. From Paddington, from Camden, from King's Cross, from

Shoreditch, from Fenchurch Street, from the depots over the water, these

vehicles arrive in numbers perfectly bewildering. Every one wants to get the

prime of the market; every salesman tells his clients that good prices depend

almost as much on early arrival as on fine quality; and thus evey cargo of fish

is pushed on to market with as little delay as need be. Pickford objurgates

Chaplin and Horne, Macnamara is wrathful at Parker, every van in in every other

van's way. Fish Street Hill and Thames Street, Pudding Lane and Botolph Lane,

Love Lane and Darkhouse Lane, all are one jam and muddle, horses entangling in

shafts, and shafts in wheels. A civilian, a non-fisherman, has no business there

at such a time; woe to his black coat or black hat, if he stands in the path of

the porters; he will have a finny sprinkling before he can well look about him;

or perhaps the tail of a big fish will flap in his face, or lobsters' claws will

threaten to grapple him.

It was always thus at Billingsgate, even before the days of

railways, and before Mr. Bunning built the present market---a structure not

without elegance on the river front; but the street arrangements are becoming

more crowded and difficult to manage every year. In the old days, when trains

and locomotives were unthought of, nearly all the fish reached Billingsgate by

water. The broad-wheeled waggons were too slow to bring up the perishable

commodity in good time; while the mail and passenger coaches, even if the

passengers had been willing (which they would not) to submit to the odour, could

not have brought up any large amount of fish. At an intermediate period, say

about 1830 or 1835, certain bold traders, at some of our seaport towns, put on

four-horse fast vans, which brought up cargoes of fish during the night, and

deposited them at Billingsgate before five in the morning; but this was a costly

mode of conveyance, which could not be safely incurred except for the best and

high-priced fish. When it became an established fact that railways could bring

up fish in any quantity, and in a few hours, from almost any port in England,

the effect was striking; the supply at Billingsgate became regular instead of

intermitting; and the midland towns, such as Birmingham amd Wolverhampton, were

placed within reach of supplies that were literally unattainable under the old

system. It used to be a very exciting scene at the river-side at Billingsgate.

As the West-end fishmongers are always willing to pay well for the earliest and

choicest fish, the owners of the smacks and other boats had a strong incentive

to arrive early at "the Gate;" those who came first were absolutely

certain of obtaining the best prices for their fish; the laggards had to content

themselves with what they could get. If there happened to be a very heavy haul

of any one kind of fish on any one day, the disproportion of price was still

more marked; for as there were no electric telegraphs to transmit the news, the

salesmen had no certain means of knowing that a large supply was forthcoming;

they sold, and the crack fishmongers bought, the first cargo at good prices; and

when the bulk of the supply arrived, there was no adequate demand at the market.

In such a state of things there is no such process as holding back, no

warehousing till next day; the fish must all be sold---if not for pounds, for

shillings; if not for shillings, for pence. Any delay in this matter would lead

to the production of such attacks upon the olfactory nerves as would speedily

call for the interference of the officers of health. In what way a glut in the

market is disposed of we shall explain presently.

It is really wonderful to see by how many routes, and from

what varied sources, fish now reach Billingsgate. The smack owners, sharpening

their wits at the rivalry of railroads, do not "let the grass grow under

their feet;" they call steam to their aid, and get the fish up to market

with a celerity which their forefathers would not have dreamed of. Take the

Yarmouth region, for instance. The fishermen along the Norfolk and Suffolk coast

congregate towards the fishing banks in the North Sea in such number that their

vessels form quite a fleet. They remain out two, three, four, or even so much as

six weeks, never coming to land in the interval. A fast-sailing cutter or

steamer visits the bank or station every day, carrying out provisions and stores

to the fishermen, and bringing back the fish that have been caught. Thus laden,

the cutter or steamer puts on all her speed, and brings the fish to land, to

Yarmouth, to Harwich, or even right to Billingsgate, according as distance, wind

and tide, may show to be best. If to Yarmouth or Harwich, a "fish

train" is made up every night, which brings the catch to Shoreditch

station, whence vans carry it to Billingsgate. There used, in the olden days, to

be fish vans from those eastern parts, which, on account of the peculiar nature

of the service, were specially exempted from post-horse duty. As matters now

are, the fishermen, when the richness of the shoal is diminished, return to

shore after several weeks, to mend their nets, repair their vessels, and refresh

themselves after their aduous labours. At all the fishing towns round the coast,

the telegraphic wire has furnished a wonderful aid to the dealers; for it

announces to the salesmen at Billingsgate the quantity and description of fish en

route, and thereby enables them to decide whether to sell it all at

Billingsgate, or to send some of it at once to an inland town. This celerity in

railway conveyance and in telegraphic communication gives rise to many curious

features in the fish-trade. Tourists and pleasure-seekers at Brighton, Hastings,

and other coast towns, are often puzzled to understand the fact that fish,

although caught and landed near at hand, is not cheaper there than in London:

nay, it sometimes happens that good fish is not obtainable either at a high

price or low. The explanation is to be sought in the fact that a market is

certain at Billingsgate, uncertain elsewhere. A good catch of mackerel off

Hastings might be too large to command a sale on the spot; whereas, if sent up

to the great centre the salesmen would soon find purchasers for it. It is, in a

similar way, a subject of vexation in the salmon districts that the best salmon

are so uniformly sent to London as to leave only the secondary specimens for

local consumption. The dealers will go to the best market that is open

for them; and it is of no avail to be angry thereat. It is said that few

families are more insufficiently supplied with vegetables than those living near

market-gardens; the cause being similar to that here under notice. Perhaps the

most remarkable fact, however, in connection with this subject is, that the fish

often make a double journey, say from Brighton to Billingsgate and back again.

The Brighton fishermen and the Brighton fishmonger do not deal one with another

so much as might be supposed; the one sends to Billingsgate to sell, the other

to buy; and each is willing to incur a little expense for carriage to insure a

certain market.

Of course the marketing peculiarities depend in some degree

on the different kinds of fish, obtainable as they are in different parts of the

sea, and under very varying circumstances. Yarmouth sends up chiefly

herrings---caught by the drift-net in deep water, or the seine-net in

shallow---sometimes a hundred tons in a night. The north of England, and a large

part of Scotland, consign more largely salmon to the Billingsgate market. These

salmon mostly come packed in ice, in boxes, of which the London and

North-Western and the Great Northern Railway Companies are intrusted with large

numbers; or else in welled steamers. The South-Western is more extensively the

line for the mackerel trade; while pilchards find their way upon the Great

Western. But this classification is growing less and less definite every year;

most of the kinds of fish are now landed at many different ports which have

railway communication with the metropolis; and the railway companies compete

with each other too keenly to allow much diversity in carriage charges. The

up-river fish, such as plaice, roach, dace, &c., come down to Billingsgate

by boat, and are, it is said, bought more largely by the Jews than by other

classes of the community. The rare, the epicurean white-bait, so much prized by

cabinet ministers, aldermen, and others, who know the mysteries of the taverns

at Blackwall and Greenwich, are certainly a piscatorial puzzle; for they are

caught in the dirty part of the Thames between Blackwall and Woolwich, in the

night-time, at certain seasons of the year, and are yet so delicate although the

water is so dirty.

With regard to the oyster trade, suffice it here to say that

the smacks and other vessels, when they arrive, are moored in front of the

wharf, to form what is called "Oyster Street." The 4th of August is

still "oyster day," as it used to be, and it is still a wonderful day

of bustle and excitement at Billingsgate; but oysters now manage to reach London

in other ways before that date, and the traditional formality is not quite so

decided as it once was. Lobsters come in vast numbers even from so distant a

locality as the shores of Norway, the fiords or firths of which are very rich in

that kind of fish. They are brought by swift vessels across the North Sea to

Grimsby, and thence by the Great Northern Railway to London. Other portions of

the supply are obtained from the Orkney and Shetland coasts, and others from the

Channel Islands. It has been known, on rare occasions, that thirty thousand

lobsters have reached Billingsgate in one day; but, however large the number be,

all find a market, the three million mouths in the metropolis, and the many

additional millions in the provinces, having capacity to devour them all. There

are some queer-looking places in Darkhouse Lane and Love Lane, near

Billingsgate, where the lobsters and crabs undergo that boiling process which

changes their colour from black to red. A basketful of lobsters is plunged into

a boiling cauldron and kept there twenty minutes. As to the poor crabs, they are

first killed by a prick with a needle, for else they would dash off their claws

in the convulsive agony occasioned by the hot water! Sprats "come in,"

as it is called, about the 9th of November: and there is an ineradicable belief

that the chief magistrate of the City of London always has a dish of sprats on

the table at Guildhall banquet on Lord Mayor's Day. The shoals of this fish

being very uncertain, and the fish being largely bought by the working classes

of London, the sprat excitement at Billingsgate, when there has been a good

haul, is something marvellous. Soles are brought mostly by trawling-boats

belonging to Barking, which fish in the North Sea, and which are owned by

several companies; or rather, the trawlers catch the fish, and then smart,

fast-sailing cutters bring the fish up to Billingsgate. Eels, of the larger and

coarser kind, patronized by eel-pie makers and cheap soup-makers, mostly come in

heavy Dutch boats, where they writhe and dabble about in wells or tanks full of

water; but the more delicate eels are caught nearer home. Cod are literally

"knocked on the head" just before being sent to Billingsgate. A

"dainty live cod" is of course not seen in the London fishmongers'

shops, and still less in the barrow of the costermonger; but, nevertheless,

there is an attempt made to approach as near to this liveliness as may be

practicable. The fish, brought alive in welled vessels, are dexterously killed

by a blow on the head, and sent up directly to Billingsgate by rail, when the

high-class fishmongers buy them at once, before attending to other fish. We may

be sure that there is some adequate reason for this, known to and admitted by

the initiated. The fish caught by the trawl-net, such as turbot, brill, soles,

plaice, haddock, skate, halibut, and dabs, are very largely caught in the

sandbanks which lie off Holland and Denmark. The trawl net is in the form of a

large bag open at one end; this is suspended from the stern of the

fishing-lugger, which drags it at a slow pace over the fishing-banks. Two or

three hundred vessels are out at once on this trade, remaining sometimes three

or four months, and sending their produce to market in the rapid vessels already

mentioned. The best kinds of trawl-fish, such as turbot, brill, and soles, are

kept apart, separate from the plaice, haddock, skate, &c., which are

regarded as inferior. The "costers" buy the haddock largely, and clean

and cure them, cut them up, fry them in oil, and sell them for poor people's

suppers. The best trawl-fish are gutted before they are packed, or the

fishmongers will have nothing to do with them. Concerning mackerel, a curious

change has taken place within a year or two. Fine large mackerel are now sent

all the way from Norway, packed in ice in boxes, like salmon, landed at Grimsby

or some other eastern port, and then sent onward by rail. The mackerel on our

own coast seem to have become smaller than of yore, and thus this new Norwegian

supply is very welcome.

All these varieties of fish alike, then, and others not here

named, are forwarded to the mighty metropolitan market for sale. And here the

reader must bear in mind that the real seller does not come into personal

communication with the real buyer. As at Mark Lane, where the cornfactor comes

between the farmer and the miller; as at the Coal Exchange, where the coalfactor

acts as an intermedium between the pit-owner and the coal-merchant; as at the

Cattle Market, where the Smithfield (so called) salesman conducts the sales,

from the grazier to the butcher---so at Billingsgate does the fish-salesman make

the best bargain he can for the fisherman, and takes the money from the

fishmonger. More than two thousand years ago, according to the Rev. Mr. Badham,

there were middlemen of this class, and men, too, of no little account in their

own estimation and in the estimation of the world. The Billingsgate salesman must

be at business by five in the morning, and his work is ended by eleven or twelve

o'clock. They all assemble, many scores of them, in time for the ringing of the

market-bell at five o'clock. Each has his stand, for which a rental is paid to

the Corporation; and as there are always more applicants for stands than stands

to give them, the privilege is a valued one. Some of these salesmen have shops

in Thames Street, or in the neighbouring lanes and alleys; but the majority have

stands only in Billingsgate. Some deal mostly in one kind of fish only, some

take all indiscriminately. In most cases (as we have said) each, when he comes

to business in the morning, has the means of knowing what kind and quantity of

fish will be consigned to him for sale. The electric telegraph does all this

work, while we laggards are fast asleep. Of the seven hundred regular

fishmongers in the metropolis, how many attend Billingsgate we do not know; but

it is probable most of them do so, as by no other means can proper purchases be

made. At any rate, the number of fishmongers' carts within a furlong or so of

the market is something enormous. The crack fishmongers go to the stalls of the

salesmen who habitually receive consignments of the best fish; and as there is

not much haggling about price, a vast amount of trade is conducted within the

first hour or two. Porters bring in the hampers and boxes of fine fish, the

fishmongers examine them rapidly, and the thing is soon done. Of course,

anything like a regular price for fish is out of the question; the supply varies

greatly, and the price varies with the supply. The salesman does the best he can

for his client, and the fishmonger does the best he can for himself.

But the liveliest scene at Billingsgate, the fun of the

affair, is when the costermongers come. This may be at seven o'clock or so,

after the "dons" have taken off the fish that command a high price.

How many there are of these costermongers it would be impossible to say, because

the same men (and women) deal in fruit and vegetables from Covent Garden, or in

fish from Billingsgate, according to the abundance or scarcity of different

commodities. Somehow or other, by some kind of freemasonry among themselves,

they contrive to learn, in a wonderfully short space of time, whether there is a

good supply of herrings, sprats, mackerel, &c., at the "Gate," and

they will flock down thither literally by the thousands. The men and boys all

wear caps---leather, hairy, felt, cloth, anything will do; but a cap it must be,

a hat would not be orthodox. The intensity displayed by these dealers is very

marked and characteristic; they have only a few shillings each with which to

speculate, and they must so manage these shillings as to get a day's profit out

of their transactions. They do not buy of the principal salesmen. There is a

class called by the extraordinary name of bommarees or bummarees

(for what reason even the "oldest inhabitant" could not tell), who buy

largely from the leaders in the trade, and then sell again to the

peripatetics---the street dealers. They are not fishmongers; they buy and sell

again during the same day, and in the market itself. The bommaree, perched on

his rostrum (which may be a salmon-box or a herring-barrel), summons a group of

costermongers around him, and puts up lot after lot for sale. There is a

peculiar lingo adopted, only in part intelligible to the outer world---a

shouting and vociferating that seems to be part of the system. The owners of the

hairy caps are eagerly grouped into a mass, inspecting the fish; and every man

or boy makes a wonderfully rapid calculation of the probable price that it would

be worth his while to go to. The salesman, or bommaree, has no auctioneer's

hammer; he brings the right palm down with a clap upon the left to denote that a

lot has been sold; and the fishy money goes from the costermonger's fishy hand

into the bommaree's fishy hand with the utmost promptness. Most of the

dried-fish salesmen congregate under the arcade in front of the market; most of

the dealers in periwinkles, cockles, and mussels (which are bought chiefly by

women), in the basement story, where there are tubs of these shell-fish almost

as large as brewers' vats; but the other kinds of fish are sold in the great

market---a quadrangular area covered with a roof supported by pillars, and

lighted by skylights. The world knows no such fishy pillars elsewhere as these;

for every pillar is a leaning-post for salesmen, bommarees, porters,

costermongers, baskets, hampers, and fish-boxes.

And now the reader may fairly ask, what is the quantity of

fish which in a day, or in a year, or any other definite period, is thus sold at

Billingsgate? Echo answers the question; but the Clerk of the Market does not,

will not, cannot. We are assured by the experienced and observant Mr. Deering,

who has filled this post for many years, that all statements on this particular

subject must necessarily be mere guesses. No person whatever is in possession of

the data. There are many reasons for this. In the first place, there are no

duties on fish, no customs on the imported fish, nor excise on that caught on

our own coasts; and therefore there are no official books of quantities and

numbers. In the second place, there is no regularity in the supply; no fisherman

or fishmonger, salesman or bommaree, can tell whether tomorrow night's catch

will be a rich or a poor one. In the third place, the Corporation of the City of

London do not charge market-dues according to the quantity of fish sold or

brought in for sale; so much per van or waggon, so much per smack or cutter, so

much per stand in the market---these are the items charged for. In the fourth

place, each salesman, knowing his own amount of business, is not at all likely

to mention that amount to other folks. Out of (say) a hundred of them, each may

form a guess of the extent of business transacted by the other ninety-nine; but

we should have to compare a hundred different guesses, to test the validity of

each. Nor could the carriers assist us much; for if every railway company, and

every boat or steamer owner, were even so communicative as to tell how many

loads of fish had been conveyed to Billingsgate in a year, we should still be

far from knowing the quantities of each kind that made up the aggregate. On

these various grounds it is believed that the annual trade of Billingsgate

cannot be accurately stated. Some years ago Mr. Henry Mayhew, in a series of

remarkable articles in the "Morning Chronicle," gave a tabulated

statement of the probable amount of this trade; and about five or six years

later, Dr. Wynter, in the "Quarterly Review," quoted the opinion of

some Billingsgate authority, that the statement was probably not in excess of

the truth. We will therefore give the figures, the reader being quite at liberty

to marvel at them as much as he likes:---

These figures nearly take one's breath away. What on earth becomes of the shells of five hundred million oysters, and the hard red coats of the eighteen hundred thousand lobsters and crabs, besides the shells of the mussels, cockles, and winkles, which are not here enumerated? Another learned authority, Mr. Braithwaite Poole, when he was goods manager of the London and North-Western Railway Company, brought the shell-fish as well as the other fish into his calculations, and startled us with such quantities as fifty million mussels, seventy million cockles, three hundred million periwinkles, five hundred million shrimps, and twelve hundred million herrings. In short, putting this and that together, he told us that about four thousand million fish, weighing a quarter of a million tons, and bringing two million sterling, were sold annually at Billingsgate! Generally speaking, Mr. Poole's figures make a tolerably near approach to those of Mr. Mayhew; and therefore it may possibly be that we Londoners---men and women, boys, girls, and babies---after supplying country folks--- eat about two fish each every average day, taking our fair share between turbot, salmon, and cod at one end of the series, and sprats, periwinkles and shrimps at the other. Not a little curious is this ichthyophagous estimate. If Mr. Frank Buckland, Mr. Francis, and the other useful men who are endeavouring to improve and increase the artificial rearing of fish, should succeed in their endeavours, we shall, as a matter of course, make an advance as a fish-eating people.

for the rest of this book, click here

W.S.Gilbert , London Characters and the Humorous Side of London Life, 1870?

Billingsgate so called, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth, after Belin King of the Britons, who built the first water-gate here in 400 B.C., styled by Fuller “the Esculine gate of London,” and has been for the last five centuries the great fish-market of the metropolis. It is built of red brick, with stone dressings and a campanile, and stands on the left bank of the river, a little below London-bridge. The market opens at 5 a.m. throughout the year, the fish being sold by tale, except in the case of salmon, which is sold by weight, and shellfish, which are sold by measure. It is one of the curious sights of London, but it is not well to go very elaborately dressed, or with too dainty ears. It is only fair, however, to say that the good old days of the “fish-fag “ are now over, and nothing worse in the way of “Billingsgate” will be heard than at any other place where rough work is being done in a hurry. Nevertheless, it requires coolness and presence of mind to pay a visit to Billingsgate with safety. Thames-street is narrow, crowded, and not over savoury. The pavements are narrow, and men are hurrying across them with boxes of oranges, for this is the centre of the Levant and Spanish fruit trade; waggons from the docks block the street; costermongers’ carts dodge in and out as best they may; everyone is intent upon business, and a man who comes on pleasure must shift for himself. Billingsgate is smelt before it is seen: there is a whiff of fresh fish and of red herrings, a tarry seaside smell which is not altogether disagreeable. Perhaps upon first visiting Bilhingsgate the feeling is one of disappointment: the show of fish is not great, for there is but little retail trade, but a little examination shows how immense is the trade carried on. At the river side are taut steamers which have just come in from the North Sea; piled up in thousands are boxes with fish from Yarmouth and Lowestoft and the eastern fishing places, and from the southern ports. There are hundreds of baskets and hampers of sprats, of herrings, of mackerel, boxes of soles and of flat fish, tons of cod, thousands of lordly turbot, and any quantity of whiting, plaice, and mullet. Besides all these there are quantities of shrimps, and, if it be the season, baskets upon basket of delicate smelt and whitebait. The river fish are represented only by salmon, and perhaps a few trout, but what a magnificent representation it is! Hundreds, nay thousands, of splendid fish which have come in ice, from Scotland principally, but some from Wales, some from Galway and the Irish rivers, some even from Norway. It is in the early morning or in the evening that Billingsgate is seen at its fullest, and perhaps the scene at night is the most characteristic. The market is well lighted, is thronged by a crowd of fishmongers and costermongers, and the din of the shouting salesmen is bewildering. If the weather has been stormy, the supply poor, the fish consequently dear, the costermonger element will soon thin out. There is no chance at such a time for them to buy fish at such a price as will enable them to sell to the working classes, and accordingly they all turn their attention to oranges, or if these are out of season, will go off for the night, and start for Covent-garden at daybreak to get a load of vegetables—perhaps even go down to a market-garden miles out, and buy the barrow-load there. Of all the population of London there are none who work longer hours for a living than do these itinerant vendors; their labour commencing at daybreak, and extending until eleven or twelve at night. NEAREST Railway Stats. ,Mansion House (Dist.), Cannon-st (S.E.), and Fenchurch. street; Omnibus Routes, Cannon-street, King William-street, Gracechurch-street, Fenchurch. street, and London-bridge; Cab Rank, Fish-street-hill

Charles Dickens (Jr.), Dickens's Dictionary of London, 1879

Billingsgate Market, Thames-street, about 300 yards east of London Bridge,

and adjoining the

west side of the Custom House, is the one only market for fish in London. Some

year since, an attempt was made to provide a second, and the Columbia Market was

built by Lady, then, Miss Burdett Coutts, with the special view of securing a

cheaper supply of fish for the benefit of the poorer classes.

Put there are few commercial problems more difficult than the establishment

of a new centre for an ancient trade. Even the Corporation themselves, to whom

Lady Burdett Coutts presently handed over her noble building, found the task

too much for them, and after struggling gallantly through a considerable period

of dismal failure, the philanthropic attempt was abandoned, and Billingsgate

resumed its undisputed sway. The derivation of its name is matter of dispute. All that is

certainly know is that the appropriation of the site to the purpose of a fish-market took place

in the year 1699 A.D., and that a fish-market it has remained ever since.

It was not impossibly the failure of the Columbia Market which suggested to

the Corporation the advisability of doing something to improve and extend the

accommodation of Billingsgate Market. At all events, on the 27th of

October, 1874, the first stone was laid of the handsome building which was to

supersede the "elegant Italian structure" of Mr. Bunning, which, with its tall

campanile, had long been one of the most conspicuous shore marks of the river

below bridge. The construction presented considerable difficulties, both from

the necessity of carrying it out without disturbance of the daily business of

the market, and from the nature of the ground on which is had to be built, and

which required an immense amount of preparation in the way of a platform of solid

concrete, 15 feet in thickness. In 1877, however, the building was completed, and on the

20th of July of that year formally opened for business. Its river façade still

adheres more or less to the Italian Gothic legend, but the campanile has

disappeared, and the building now presents a uniform frontage of two lofty

storeys, the centre portion being thrown a little back. The wings,

which are, perhaps, artistically speaking, somewhat small in proportion to the central block, are occupied by taverns, at

each of which is a daily fish ordinary.

All along the front runs a broad floating story, alongside of which come

the smaller craft by which the water-borne fish are brought up the river, and

which vary in size and rig from the specially built

steamer of more than 200 tons register, whose cargo has been collected from the

smacks of the North Sea, to the little open barge in which cod or salmon has

been lightered from the big sea-going ships in the docks of Victoria or Millwall.

These North Sea steamers are a very special feature in the

Billingsgate trade, not only for their novelty, but in themselves. They were

originally started by Messrs. Hewett, the largest salesmen in the market, and

till recently the only firm which as yet had impressed steam into the service of

the water-borne trade. They are still the largest fish-steamer owners and their

vessels, six in number, are the largest in point of tonnage, averaging something

under 200 tons register each. But a new joint-stock company has within the last

few months started at Grimsby, with four steam vessels averaging a little over

100 tons each. The vessels themselves are somewhat curiously built, with a

shear almost like that of a Chinese junk, which, indeed, with the addition of a

small poop and top-gallant forecastle, they would not a little resemble. They

have considerable beam for their length, and are strongly and bluffly built,

their cargo being heavy, and the weather they have to encounter often of the

wildest. The engine-room is placed aft, and is strongly housed in to a

considerable height above the deck, which is frequently swept fore and aft for

hours together by seas which, without such precaution, would speedily drown her

fires, and send ship and cargo together to the feeding grounds from which the

latter had been so recently taken. In spite, however, of their heavy build,

they can develop a very fair turn of speed, and have frequently been known to

make the round voyage from Billingsgate to the North Sea and back twice in the

course of a single week. Arrived on their cruising ground, the loading is an

arduous, and but too often a highly dangerous operation. The smacks themselves in

which the fish have been caught do not venture alongside, but send

their "trunks" of fish in small open boats, from which they are hove on to

the steamer's deck. Even so, however, the transhipment of a number of heavy

boxes from a little dancing cockle-shell of a craft is no easy or safe task, and numbers of lives are lost by

the capsizing of an overloaded boat, or by a momentary carelessness in fending

her off, as the steamer lurches suddenly down upon her. In comparatively smooth water, a boat will

discharge on either side of the ship. In rougher weather only

one will venture alongside at a time to leeward. But it must be very heavy

weather, indeed, in which these hardy fellows abandon the attempt, and the steamer loses her voyage altogether. The loaded "trunks"

safely on board,

the next operation is to hand over to the discharged boat a fresh supply of

empty trunks with a corresponding quantity of fresh ice - a most important

article, without which but a very small proportion of the present trade in fish

could be carried on.

The steamer's load collected, and her supplies of ice and

empty trunks duly distributed, the next thing is to catch her tide at the

river's mouth. This is a most important point, especially in warm weather.

Missing the tide means missing the market, and missing the market may but too

possibly at such time mean the sacrifice of the greater portion, if not

the whole, of the cargo, involving sometimes a loss of hundreds of pounds.

On this point, indeed, a good deal of misapprehension exists. People who read in

the papers of the "seizure" at Billingsgate of so many tons of fish as

"unfit for human

food," are apt to look upon tine salesmen as deliberately engaged in a chronic

conspiracy against the public health. The task of detecting unsound fish is

not left to the market authorities but is diligently carried out by the

salesmen themselves, who at once set aside any trunk to which the slightest

suspicion can attach, and send for the fish-meter to inspect it and deride

upon its fate. If pronounced tainted, it is consigned to a condemned cell in the

hold of the landing-stage, whence it is cleared out by the contractors in whose charge it

passes down the river again, for conversion into manure.

The sound fish are then carried ashore by the licensed porters,

a class of men who probably make more money in less time than any unskilled

labourers in Europe. A Billingsgate porter's license costs but 2s. 6d.,

including the numbered brass badge with the City arms and the words Billingsgate Market which

he wears upon his arm. A hard-working man will earn on favourable days as much as

20s., and that by 10 o'clock in the

morning, leaving the rest of the day at his disposal.

The landing process begins every morning, summer and winter,

at 5 a.m., when the tolling of the big bell announces the opening of the market, and a

rush takes place to secure the earliest sales. The of these falls almost as a matter

of prescription to Messrs. Hewett, who for years past have prided themselves upon

putting up their first lot before the last stroke of the hour has ceased to vibrate.

Besides the large steamers, of which there will be two or sometimes three at a

time, the landing-stage is beset with a swarm of sailing, rowing, and towing craft of

all sizes, rigs, and builds; handy sea-going cutters and smacks direct from the

fishing-ground; barges with consignments of salmon from the big steamers trading from

Norway to the Millwall Docks, or of cod from the far-off banks of Newfoundland; saucy

little sprat-boats, open row-boats with shrimps or river fish, and great solid

Dutch schuyts - Billingsgatice "skoots" - only just less broad than they

are long, and with round bluff bow, and equally

round bluff stern. Exquisitely clean and tidy, however, are these

eccentric-looking

craft, with their wriggling cargoes of eels piled in one great slimy mass in their

roomy holds. With many of them even paint - and none but your Dutchman; could appreciate

your true Hollander's devotion to the paint-pot - fails to attain the standard aimed

at by Mynheer of an eel-schuyt. The whole craft will be built of finest oak,

scraped and polished like the floor of an old-fashioned French drawing-room, till

it is slippery to the touch as the eels it encloses, and as bright as the

glowing copper bolts on which rottenstone and wash-leather seem to be

unceasingly at work from morn to eve of seven days a week.

Inside the market the scene is animated to the verge of

obstreperousness. The great hall in which the sales take place, and which

occupies the whole ground-floor of the centre building, is let off in 140 "stands," at a

rate per week which, by the bye-laws of the market, sanctioned by the Board of Trade, is

not to exceed 9d. per superficial foot. At each of the standings

sales are busily going on, in many cases by auction, though how in such cases

the bids of individual buyers ever reach the ear of the auctioneer through

the Babel-like storm which is raging around is one of those things which no

fellow not himself a fish-salesman, can hope to understand. The huge piles of

trunks which have arrived by water, and which for the first hour or so are

continually augmenting under the stream of fresh supplies poured in by the

porters, are supplemented

by still heavier arrivals from the

landward side, where for hundreds of yards - east, west, and north of the market - Thames-street and its

tributaries

are blocked by a solid mass of waggons, vans, and railway machines. The

chief portion of the supplies of this kind comes in the machines, which are in effect mighty

packing-cases, 12 or 15 feet long, by 6 or 8 feet wide, and

about 3 feet deep, solidly clamped and bound with iron, and with heavily

padlocked lids opening on hinges, the inside filled with a solid mass of

fish closely-packed in finely-ground ice. The greater number of these machines

come up by rail from Grimsby and elsewhere upon ordinary open

trucks, from which they are hoisted out on to lorries constructed for the

purpose. Some, however, especially of those belonging to the Great Eastern

line, are themselves mounted on wheels, but this plan seems to be giving way

to the other. The total weekly supply of the market averages by water - 800 to

850 tons, and by land as nearly as possible double that amount, and as the

whole of this enormous mass has to be carried on men's shoulders from ship

or machine to salesman's stall, there to be disposed of in some four hours

or so, more or less, among the thousands of fishmongers and costers, large and small, from the

swell tradesman of the West End, whose weekly bill for salmon alone will not

unfrequently cast up in three figures, to the itinerant, who will trundle off his

hand-barrow of "offal" for after-dark disposal in Clare Market or the

New Cut, and then all

carried back again for distribution among the vans, carts, and barrows of the

purchasers, some faint idea may readily be formed of the bewildering turmoil of the

scene. Even this, however, is not all, for Billingsgate supplies not only

London but a very large portion of England. From Brighton to Birmingham, from

Epping to Exeter, the supply is furnished almost exclusively from Billingsgate, whilst a large proportion of the market

supplies are sold

twice over ; the costers and smaller fishmongers being unable to take the large

lots into which the stock is divided by the original salesman, and purchasing

their modest supplies of the "Bummaree," who divides his purchases into

parcels of sometimes even two or three fish. The market is at its height from 5

am. to about 9, by which time the greater part of the morning supply has

been cleared off; but the market remains nominally open until 3 p.m., up to

which period there is always a chance of the arrival of some belated craft with additional supplies.

It must not he supposed, however, that these chance arrivals are

allowed to

take any one by surprise. From whatever point of the shore the approach of any

fish-laden craft is first noted, the electric wire conveys the intelligence

forthwith to Billingsgate; but even this does not satisfy the exigencies of

the modern fish trade, and large numbers of pigeons are maintained for the

express purpose of communicating with the shore from points on the open sea,

to which the ubiquitous wire has not even yet penetrated.

Not the least curious feature in the transactions of

Billingsgate is the

classification of its scaly ware. That the mighty cod, the lordly turbot, the

royal salmon, the eccentric skate, the halibut beloved of Israel, the

mullet (woodcock of the sea), the delicate sole of ordinary domestic

life, and half a score more should vote themselves the aristocracy of the market

under the title of "prime" fish is natural enough, though even

philichthists might be found in whose vocabulary the snub-nosed grey-mullet

at all events would hardly take that rank ; but why the delicate plaice and

toothsome haddock should be contemptuously ranked as offal is a question hardly to be solved on

gastronomic grounds. Probably the true solution is the financial one, and if turbot and salmon should ever

become plentiful enough to be

thrown upon the market at a penny or so apiece, they, too, would very shortly

lose caste. So cheap at all events are the despised fish at Billingsgate, that

even at the low prices at which they may be had in the shops by the

understanding marketer, they are believed by those versed in such matters to

produce a larger profit than anything else that wears fins. A haddock which will be offered for sale at a West End fishmonger's for a couple of shillings,

and for which even an East End coster will ask and obtain sixpence or eightpence,

has very likely been purchased in that morning's market for twopence or

even less. Very often they are not disposable to the day's market even at that

price, and they are then bought up for smoking.

Meanwhile,in the great dungeon-like basement below the

market, a somewhat similar scene to that above is being enacted with the day's

supply of shell-fish. The pressure is indeed not so great, the accommodation

for this branch of the business being rather in excess of the demand, but

the scene is lively enough nevertheless, and hundreds of bushels of crabs and

lobsters, prawns and shrimps, cockles, mussels, whelks, and winkles, change

hands under the flaring gas-jets, which here, a dozen feet or more below the

river level, afford, with the exception of a few dim glass bulls'-eyes in the

pavement of the market above, the only available illumination.

In a side chamber on this floor is the boiling

establishment, where the shell-fish which have been purchased in the market can

be prepared for consumption. The boiling apparatus consists of a row of eight or ten

coppers, each encased in a strong iron

jacket, into which can be introduced at will the steam from the great central

boiler. The fish are placed in a kind of crate holding about three

bushels each, and are immersed in the coppers, the periods varying from ten to

twenty minutes or more, according to the size of the individual fish.

Very few shrimps or prawns, however, find their way to the Billingsgate

boiling-house, the great majority being operated upon on their way to market

on board the smacks. The staff of the market includes about eleven

hundred licensed porters, besides constables, detectives, clerks, &c. and

the business, rough and riotous as it is, is conducted, so far as the

official personnel is concerned, with machine-like precision and

punctuality. The utmost care, too, is taken to ensure the most scrupulous

cleanliness throughout the building.

Charles Dickens (Jr.), Dickens's Dictionary of the Thames, 1881

see also Richard Rowe in Life in the London Streets - click here

BILLINGSGATE MARKET, LOWER THAMES STREET ... The great fish market of London, where fish have been sold since 1351. The Market opens at 5 a.m. throughout the year.

Reynolds' Shilling Coloured Map of London, 1895

Victorian London - Publications - Social Investigation/Journalism - Twice Round the Clock, or The Hours of the Day and Night in London, by George Augustus Sala, 1859[-back to menu for this book-]

[-9-] FOUR O’CLOCK A.M.—BILLINGSGATE MARKET.

READER, were you

ever up all night? You may answer that you are neither a newspaper editor, a

market gardener, a journeyman baker, the driver of the Liverpool night mail,

Mrs. Gamp the sicknurse, the commander of the Calais packet, Professor Airey,

Sir James South, nor a member of the House of Commons. It may be that you live

at Clapham, that one of the golden rules of your domestic economy is “gruel at

ten, bed at eleven,” and that you consider keeping late hours to be an

essentially immoral and wicked habit,—the immediate prelude to the career and

the forerunner of the fate of the late George Barn-well. I am very sorry for

your prejudices and your susceptibilities. I respect them, but I must do them

violence. I intend that— bon gre, mal

gre — in spirit, if not in actual corporeality, you should stop out not

only all night but all day with me; in fact, for the space of twenty-four hours,

it is my resolve to prohibit your going to bed at all. I wish you to see the

monster LONDON in the varied phases of its outer and inner life, at every hour

of the day-season and the night-season; I wish you to consider with me the giant

sleeping and the giant waking; to watch him in his mad noonday rages, and in

his sparse moments of unquiet repose. You must travel TWICE ROUND THE CLOCK

with me; and together we will explore this London mystery to its [-10-] remotest

recesses—its innermost arcana. To others the downy couch, the tasselled

nightcap, the cushioned sofa, the luxurious ease of night-and-day rest. Ours be

the staff and the sandalled shoon, the cord to gird up the lions, the palmer’s

wallet and cockle-shells. For, believe me, the pilgrimage will repay fatigue,

and the shrine is rich in relics.

Four o’clock in the

morning. The deep bass voice of Paul’s, the Staudigl of bells, has growlingly

proclaimed the fact. Bow church confirms the information in a respectable

baritone. St. Clement’s Danes has sung forth acquiescence with the well-known

chest-note of his tenor voice, sonorous and mellifluous as Tamberlik’s. St.

Margaret’s, Westminster, murmurs a confession of the soft impeachment in a

contralto rich as Alboni’s in “Stridi la vampa;” and all around and about

the pert bells of the new churches, from evangelical Hackney to Puseyite

Pimlico, echo the announcement in their shrill treble and Soprani.

Four o’clock in the

morning. Greenwich awards it,—the Horse Guards allow it—Bennett, arbiter of

chronometers and clocks that, with much striking, have grown blue in the face,

has nothing to say against it. And that self-same hour shall never strike again

this side the trumpet’s sound. The hour itself being consigned to the

innermost

pigeon-hole of the Dead Hour office—(a melancholy charnel-house of misspent

time is that, my friend)—you and I have close upon sixty minutes before us ere

the grim old scythe-bearer, the saturnine child-eater, who marks the seconds and

the minutes of which the infinite subdivision is a pulsation of eternity, will

tell us that the term of another hour has come. That hour will be five a.m., and

at five it is high market at Billingsgate. To that great piscatorial Bourse we,

an’t please you, are bound.

It is useless to disguise

the fact that you, my shadowy, but not the less beloved companion, are about to

keep very bad hours. Good to hear the chimes at midnight, as Justice Shallow and

Falstaff oft did when they were students in Gray’s Inn; but four and five in

the morning! these be small hours indeed: this is beating the town with a

vengeance. Were it winter, our bedlessness would be indefensible; but this is

still sweet summer time.

But why, the inquisitive

may ask—the child-man who is for ever cutting up the bellows to discover the

reservoir of the wind—why four o’clock a.m.? Why not begin our pilgrimage at

one a.m., and finish the first half at midnight, in the orthodox

get-up-and-go-to-bed man-[-11-]ner? Simply because four a.m. is in reality the first

hour of the working London day. The giant is wide awake at midnight; he sinks

into a fitful slumber about two in the morning: short is his rest, for at four

he is up again and at work, the busiest bee in the world’s hive.

The child of the Sun, the

gorgeous golden peacock, strutting in a farmyard full of the Hours, his hens,

now triumphs. It is summer and more than that, a lovely summer morning. The

brown night has retired, and the meek-eyed moon, mother of dews, has

disappeared:

the young day pours in

apace; the mountains’ misty tops are swelling on the Sight, and brightening in

the sun. It is the cool, the fragrant, and the silent hour, to meditation due

and sacred song; the air is coloured, the efflux divine turns hovels into

palaces, and shoots with gold the rags of beggars.

“The city now doth like

a garment wear

The beauty of the morning

Never did Sun more

beautifully steep

In his first splendour,

valley, rock, or hill.

Ne’er saw I, never felt,

a calm so deep.

The River glideth at its

own sweet will;

Dear God! the very houses

seem asleep,

And all that mighty Heart

is lying still.”

I know that the

acknowledgment of one’s quotations or authorities is going out of fashion.

Still, as I murmur the foregoing lines as I wander round about the Monument and

in and out of Thames Street, waiting for Billingsgate-market time to begin, a

conviction grows upon me that the poetry is not my own; and in justice to the

dead, as well as with a view of sparing the printer a flood of inverted commas,

I may as well confess that I have been reading Mr. James Thomson and Mr. William

Wordsworth on the subject of summer lately, and that very many of the flowery

allusions to be found above, have been culled from the works of those pleasing

writers.

Non omnes moriar. Though the so

oft-mentioned hours be asleep, and the river glideth in peace, undisturbed by

penny steamboats, the mighty heart of Thames Street is anything but still. The

great warehouses are closed, ‘tis true; the long wall of the Custom House is

a huge dead wall, full of blind windows. The Coal Exchange (which edifice, with

its gate down among the dead men in Thames Street, and its cupola, like a

middle-sized bully, lifting its head to about the level of the base of that

taller bully the Monument, is the neatest example of an architectural “getting

up stairs” that I know)—the Coal Exchange [-12-] troubles not its head as yet about

Stewarts or Lambtons, Sutherlands or Wallsend. The moist wharfs, teeming with

tubs and crates of potter’s ware packed with fruity store, and often

deliciously perfumed with the smell of oranges, bulging and almost bursting

through their thin prison bars of wooden laths, are yet securely grated and

barred up. The wharfingers are sleeping cosily far away. But there are shops and

shops wide open, staringly open, defiantly open, with never a pane of glass in

their fronts, but yawning with a jolly ha! ha! of open-windowedness on the

bye-strollers. These are the shops to make you thirsty; these are the shops to

make your incandescent coppers hiss; these are the shops devoted to the

apotheosis and apodeiknensis (I quote Wordsworth again, but Christopher, not

William) of Salt Fish—

“Spend Herring first,

save Salt Fish last,

For Salt Fish is good when

Lent is past.”

So old Tusser. What piles

of salted fish salute the eye, and make the mouth water, in these open-breasted

shops! Dried herrings, real Yarmouth bloaters, kippered herrings, not forgetting

the old original, unpretending red herring, the modest but savoury “soldier”

of the chandler’s-shop! What flaps of salt cod and cured fishes to me unknown,

but which may be, for aught I know, the poll of ling which King James the First

wished to give the enemy of mankind when he dined with him, together with the

pig and the pipe of tobacco; or it may be Coob or Haberdine! What are Coob and

Haberdine? Tell me, Groves, tell me, Polonius, erst chamberlain and first

fishmonger to the court of Denmark. Great creels and hampers are there too, full

of mussels and periwinkles, and myriads of dried sprats and cured

pilchards—shrunken, piscatorial anatomies, their once burnished green and

yellow panoplies now blurred and tarnished. On the whole, each dried-fish shop

is a most thirst-provoking emporium, and I cannot wonder much if the

blue-aproned fishmongers occasionally sally forth from the midst of their fishy

mummy pits and make short darts “round the corner” to certain houses of

entertainment, kept open, it would seem, chiefly for their accommodation, and

where the favourite morning beverage is, I am given to understand, gin mingled

with milk. It is refreshing, however, to find that the fragrant berry of Mocha

(more or less adequately represented by chicory, burnt horse-beans, and roasted

corn)—that coffee, the nurse of Voltaire’s wit, the inspirer of Balzac’s

brain; coffee, which Madame de Sevigné pertly predicted [-13-] would “go out” with

Racine, but which nevertheless has, with astonishing tenacity of vitality,

“kept in” while the pert Sevigne and the meek Racine have quite gone out

into the darkness of literary limbo—is in great request among the fishy men of

Billingsgate. Huge, massive, blue and white earthenware mugs full of some brown

decoction, which to these not too exigent critics need but to steam, and to be

sweet, to be the “coffee as in France,” whose odoriferous “percolations”

the advertising tradesmen tell us of, are lifted in quick succession to the

thirsty lips of the fishmen. Observe, too, that all market men drink and order

their coffee by the “pint,” even as the scandal-loving old ladies of the

last century (ladies don’t love scandal now-a-days) drank their tea by the

“dish.” I can realise the contempt of a genuine Billingsgate marketeer for

the little thimble-sized filagree cups with the bitter Mocha grouts at the

bottom, which, with a suffocating Turkish chibouque, Turkish pachas and

attar-of-roses dealers in the Bezesteen, offer as a mark of courtesy to a Frank

traveller when they want to cheat him.

Close adjacent is a narrow

passage called Darkhouse Lane, and here properly should be a traditional

Billingsgate tavern called the “Darkhouse.” There is one, open all night,

under the same designation, in Newgate Market. Hither came another chronicler

of “twice round the clock” with another neophyte, to show him the wonders

of the town, one hundred and fifty years ago. Hither, when pursy, fubsy,

good-natured Queen Anne reigned in England, and followed the hounds in

Windsor’s Park, driving two piebald ponies in a chaise, and touched children

for the “evil,” awing childish Sam Johnson with her black velvet and her

diamonds, came jovial, brutal, vulgar, graphic Ned Ward, the “ London Spy.”

Here, in the “ Darkhouse,” he saw a waterman knock down his wife with a

stretcher, and subsequently witnessed the edifying spectacle of the recreant

husband being tried for his offence by a jury of fishwomen. Scant mercy, but

signal justice, got he from those fresh-water Minoses and Rhadamanthuses.

Forthwith was he “cobbed “—a punishment invented by sleeveboard~vielding

tailors, and which subsequently became very popular in her Majesty’s navy.

Here he saw “fat, motherly flatcaps, with fishbaskets hanging over their

heads instead of riding-hoods,” with silver rings on their thumbs, and pipes

charged with “mundungus” in their mouths, sitting on inverted eel-baskets,

and strewing the flowers of their exuberant eloquence over dashing young town

rakes who had stumbled into Billingsgate to finish the night—disorderly blades

in [-14-] laced velvet coats, with torn ruffles, and silver-hilted swords, and plumed

hats battered in scuffles with the watch. But the town-rakes kept comparatively

civil tongues in their heads when they entered the precincts of the Darkhouse.

An amazon of the market, otherwise known as a Billingsgate fish-fag, was more

than a match for a Mohock. And here Ned Ward saw young city couples waiting for

the tide to carry them in a tilt-boat to Gravesend; and here he saw bargemen

eating broiled red-herrings, and Welshmen “louscobby” (whatever that

doubtless savoury dish may have been, but there must

have been cheese in it) ; and here he heard the frightful roaring of the

waters among the mechanism of the piers of old London Bridge. There are no

waterworks there now; the old bridge itself is gone; the Mohocks are extinct;

and we go to Gravesend by the steamer, instead of the tilt-boat ; yet still, as

I enter the market, a pleasant cataract of “chaff” between a fishwoman and a

costermonger comes plashing down—even as Mr. Southey tells us that the waters

come down at Lodore—upon my amused ears; and the conviction grows on me that

the flowers of Billingsgate eloquence are evergreens. Mem.: To write a

philosophical dissertation on the connection between markets and voluble

vituperation which has existed in all countries and in all ages. ‘Twas only

from his immense mastery of Campanian slang that Menenius Agrippa obtained such

influence over the Roman commons; and one of the gaudiest feathers in Daniel

O’Connell’s cap of eloquence was his having “slanged” an Irish

market-woman down by calling her a crabbed old hypothenuse!

Billingsgate has been one

of the watergates or ports of the city from time immemorial. Geoffrey of

Monmouth’s fabulous history of the spot acquaints us that “ Belin, a king of

the Britons, about four hundred years before Christ’s nativity, built this

gate and called it ‘Belinsgate,’ after his own calling;” and that when he

was dead, his body being burnt, the ashes in a vessel of brass were set on a

high pinnacle of stone over the said gate. Stowe very sensibly observes, that

the name was most probably derived from some previous owner, “happily named

Beling or Biling, as Somars’ Key, Smart’s Wharf, and others, thereby took

the names of their owners.” When he was engaged in collecting materials for

his “Survey,” Billingsgate was a “large watergate port, or harborough for

ships and boats commonly arriving there with fish, both fresh and salt,

shellfish, salt, oranges, onions, and other fruits and roots, wheat, rye, and

grain of divers sorts, for the service of the city, and the parts of this realm

adjoining.” [-15-] Queenhithe, anciently the more important watering-place, had

yielded its pretensions to its rival. Each gives its name to one of time city

wards.

Some of the regulations